Parasite: a global flow from north to south

In May this year, a South Korean film, Parasite, won the Palme d’Or at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival. It is the first Korean film receiving this award. Parasite has received worldwide acclaims and been sold to 192 countries and regions, which is undoubtedly a huge success exemplifying the global flow from south (poorer countries) to north (wealthier countries).

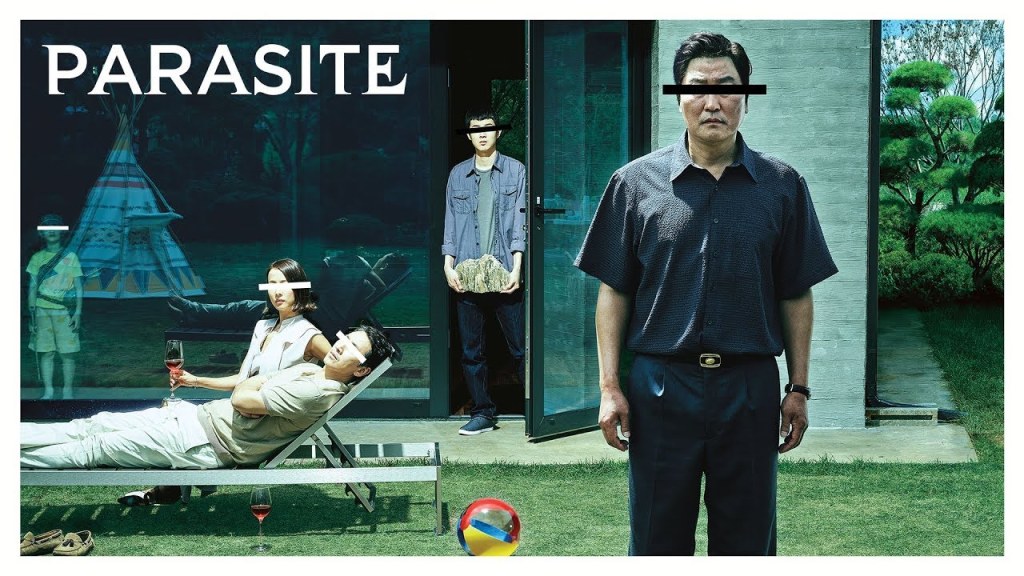

Parasite tells the story of a family of four who live in a shabby semi-basement rental house. After Ki-woo, the son, became the English tutor of a wealthy family, he managed to get all of his family a job in that lavish house like parasites. The film reflects the increasingly serious chasm between the rich and the poor, which is also a big issue existing in many other countries. For example, a Japanese flim, shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or last year also mirrors the lives of poverty.

Parasite is a definitely cultural hybridization. It “borrows the idea and practice of the blockbuster and adapting them to local circumstances” (Berry, 2003). In terms of the theme, I think what Parasite wants to convey is similar to the Great Gatsby, a film released in 2013 about the hypocritical wealthy class and the poor class who managed to become a billionaire. And then Parasite narrates it in a Korean style to de-westernize and create something for the local market.

However, Parasite not only gains national box success, but also wins worldwide attention. Besides the film’s universal theme, the director Bong Joon-ho can also be attributed to its global success. Bong is famous to the foreign audience for his film Okja which is a 2017 South Korean and American action-adventure film. And Parasite is the director’s first film made fully within the Korean system in a decade, since 2009’s Mother. As a commercial film, it thinks local but acts global. An Australian website, filmink, commented that this is Bong’s best film since 2003’s Memories of Murder, and makes a good case for being the first out-and-out classic of Korean cinema since 2016’s The Handmaiden.

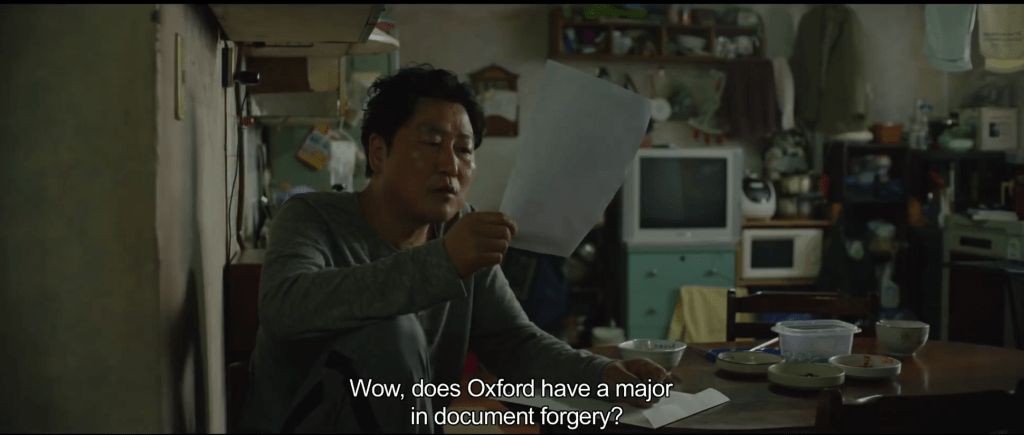

In addition, it worth noticing that when Parasite was playing overseas the subtitles also tried to approach the cultural proximity to let the foreign audience makes sense better. For example, “Kakao talk” which is a popular Korean social media app is translated into What’s app when it is filmed in Australia and “Seoul University”, the best university in South Korea, is translated into the more well-known “Oxford”.

As Arjun Appadurai (1996) noted, globalization is not a single process, but a multiplicity of localized events as different cultures are brought into contact. The blockbusters from Hollywood become increasingly focused on spectacular scene, advanced digital technology and thrilling plot, and the cost is that the stories became homogeneous and simple. Meanwhile, Hallyuwood’s de-westernization becomes more and more attractive not only to the local but also to the worldwide audience. Therefore, Korean waves make the global film market heterogeneous as the audience from all the countries become more open to the different culture.

References:

-Berry, C 2003, ‘“What’s big about the big film?”: “de-Westernizing” the blockbuster in Korea and China’, in J. Stringer (ed.), Movie Blockbuster, Routledge, London, pp. 217-229.

-Appadurai, A 1990, ‘Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy’ Theory, Culture & Society, Vol. 7 no. 2, pp.295-310.

-Parasite By Andrew Blackie 2019 https://www.filmink.com.au/reviews/parasite/ [Viewed August 30]